Episode Transcript

JOHN HENRY: This is Open for Business, a new branded podcast from eBay and Gimlet Creative about building a business from the ground up. I’m John Henry. I started and sold my own business a few years back. And after that, I founded a startup accelerator in Harlem, New York. It’s called Cofound Harlem.

JOHN HENRY: This is Open for Business, a new branded podcast from eBay and Gimlet Creative about building a business from the ground up. I’m John Henry. I started and sold my own business a few years back. And after that, I founded a startup accelerator in Harlem, New York. It’s called Cofound Harlem.

Cofound Harlem seeks out promising new companies and we help them grow. We don’t take any equity from them but we ask one thing in exchange, that they agree to headquarter their companies back in Harlem after the program is over.

And that’s where we are now. It’s demo night for Cofound Harlem.

JOHN HENRY: I’m on stage. We’re presenting our first class of startups to a small theater filled with business owners, entrepreneurs, would-be entrepreneurs.

The crowd is diverse... Different races, different ages. In the audience, I see many familiar faces, folks I know from living and working in Harlem. The guy that all these people are waiting around to see is Nsi Obutetekudo.

JOHN HENRY: Nsi is the co-founder of Alley, a network of coworking spaces in New York City that are meticulously designed and curated. Alley raised 16 million dollars in venture funding last year. Nsi fits a certain prototypical entrepreneurial profile - an extreme, intense drive.

JOHN HENRY: Which I think is exemplified in this one moment from our conversation, live on stage. I asked if he had any advice for entrepreneurs just starting out. And he answered my question by talking about a trip he took to Mount Kilimanjaro.

Now, quick note. He uses some explicit language here so if you’re listening with kids, I’d suggest earbuds for the next 90 seconds:

Nsi Obotetukudo: I climbed Kilimanjaro and uh... I didn’t take any medication for the altitude sickness. And the idea there is that me being a bit of a masochist, I wanted to see like when my body would break and all that. Um, so, this is going to get very graphic but I’m going to share it with you anyway. There was a moment there, there’s like the summit you have just before the sun is, is rising. You’re supposed to, leave your, leave your camp and you’re breaking out to, to complete the summit. This is maybe an hour or two, maybe three hours before the sunrise because you want to be at the top of the mountain to see the sunrise. So, that’s when my altitude sickness really kicked in. So basically, ten minutes into it, I shit on myself. Excuse my language. Like, literally, I had shit in my pants. And I was still climbing up. It was cold. And, I’m like, I’m a grown ass dude and I am, I have shit on my pants. Um, it was bad. I, I passed out maybe two or three times standing. And the folks who were with me didn’t realize because, you know, I was keeping pace. But the biggest thing for me was, during that time was, being mindful that I could breathe, so the thought is like: If I can breathe, everything is going to be fine. If I can breathe, everything is going to be fine. Even if I don’t remember what just happened the last minute ago, like, I’m here now, ok cool. We’re going to keep going. If you can breathe, everything is going to be fine.

JOHN HENRY: That metaphor for entrepreneurship resonates with me. You do feel at times like you’re climbing a mountain and it does get graphic and messy and you wonder: am I going to make it?

And so, something I think about all the time is: Why do I and so many other people sign up for the life of a business owner, or of an entrepreneur?

Starting and running your own business is... grueling. So what is it about a person that makes them want to do it? And also, what makes a person good at it? And whatever that is, are you born with it?

Each week, on this podcast, we’ll tackle a different topic that entrepreneurs wrestle with when starting and running their own business. It’s the stuff I wish I knew when I was just starting my first company.

And today’s episode: What makes a successful entrepreneur, and if you are one, were you born that way?

CORRI MCFADDEN: I’d sell anything you give me. I sold a flying machine like it had, like, propellers on it. Like you run down a field and fly.

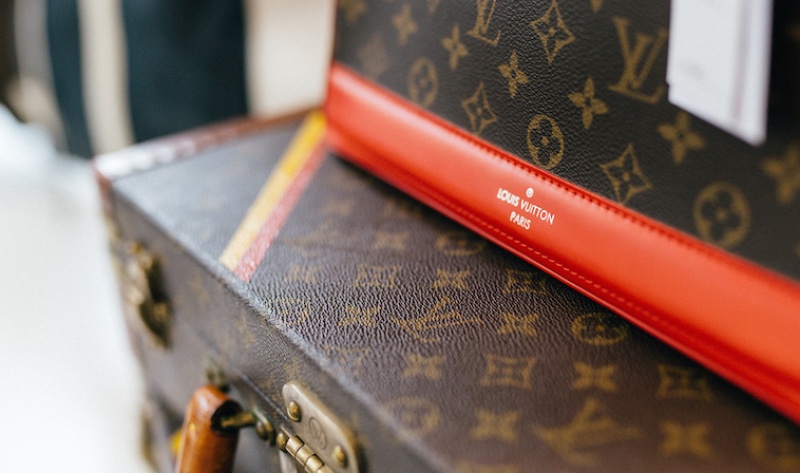

JOHN HENRY: This is Corri McFadden, business owner, entrepreneur. We’re in Corri’s office right now in Chicago. Today, Corri is founder of EDROP-OFF, a luxury consignment store that she started on eBay more than a decade ago...

EDROP-OFF OFFICE: We got two Balanciaga bags... sweet! We love that. Are they the city bags?

JOHN HENRY: Corri has grown EDROP-OFF into a multi-million dollar business on eBay. And here’s how it works... Customers bring in their designer clothing or handbags or jewelry to her store in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago.

EDROP-OFF authenticates that the designer stuff is actually design, her team photographs them for sale online, they determine the value and then, they put the items up for sale on eBay. Once it sells, EDROP-OFF keeps a commission. Today, there are lots of young women... and a couple young men... running her store.

But it wasn’t always this way. Corri is self-financed. She took out a couple loans early on, but that’s it. And when she first set up her eBay site and opened her doors twelve years ago, there were no guarantees, no indication that this big idea of hers was going to take off or even make it at all…

CORRI MCFADDEN: I remember opening up the door and the first person coming in for a drop off: A pair of rollerblades, and I’m like, ‘Hello! You want to sell them on eBay, cool!’ Like, and then followed by - after he walked out - and then another guy walked in and told me this is the stupidest idea that he had ever seen and I was going to fail, and me thinking like, ‘Oh my God!’ And those were my two clients in the first day and I’m like, shit! A roller blade and someone telling me I was going to fail. This is not... How am I going to pay this rent? Um, I sold, I mean I remember someone brought in a taxidermied long fish. It had a sword on it. I’m like, ‘Why did I take this?’ But it was going to sell for $500 and I’m like, ‘I’ll sell it.’ And then I have to get it ready for freight and pallet this fish and then the fin broke off. Of course! And then I like had to eat it and I was like, oh my god! It was just every transaction was so much work and then I would sell a Chanel bracelet and it would go for $600 and I’m like, boom, quick easy money! Any time someone would come in with something designer that’s who I started focusing on. Those were the clients that I started listening to. Those were the clients I started building relationships to.

JOHN HENRY: Corri has come a long way since the days of selling rollerblades and flying machines. She told us that last year, EDROP-OFF sold roughly five million dollars of inventory. That is, designer bags and clothing and shoes, almost all of it on eBay.

JOHN HENRY: How long have you been bringing ideas into fruition, like what’s the earliest memory that you have of that?

CORRI MCFADDEN: Um, third grade. It was when Lisa Frank was big and stickers were, like, it. And so I started a sticker trading company during recess and so I used to be who you traded stickers through. I built this insane arsenal of like the best stickers. You remember like the big ones that would be out of the machine that you’d pay a dollar for at the skating rink? And in order to trade stickers you belonged to the club and I’m the one that would barter the trade. And so I would deem if the trade was fair or not and you would pay me in a commission sticker to barter the trade.

JH OFF MIC: So you get paid in stickers.

CORRI: So I get paid in stickers.

JOHN HENRY: Even before the sticker bartering business, there were the intricate paper flowers she made and sold. And then later, the Brittany Hills Beauty Pageant...

CORRI MCFADDEN: Our subdivision was called Brittany Hills and I had the Brittany Hills beauty pageant. We always wanted to be in a pageant when we were in junior high. You would get those packets in the mail and then you would have to go fundraise. And my mom’s like, ‘You’re not.’ Like, ‘No, we’re not doing this.’ So I was like, ‘Well I’ll make our own pageant’. And I organized the whole pageant with different categories and I remember stapling up sheets in my parents’ basement to make dressing rooms and everyone paid an entry fee. It was 25 dollars which was a lot of money and, but that was to cover the rose at the end that you got with your sash. I glittered all the sashes. I mean it was like a whole project that I worked on for three months and had this beauty pageant. I’ve always recognized where there’s a void or a niche and I’ve always tried to like cater to that, my entire life.

JOHN HENRY: This seems to be a hallmark of entrepreneurs. It’s something you hear from a lot of them. It’s something I think about myself: Entrepreneurs have always been entrepreneurs. Nsi, the guy at the top of the show with the Mount Kilimanjaro story, he sold bootleg Dr. Dre CD’s in junior high school. I sold candy and those Lance Armstrong LIVESTRONG bracelets after school. It just feels like it’s something we were born to do.

JOHN HENRY: You co-authored a study with the following title: Is the Tendency to Engage in Entrepreneurship Genetic? So, yes or no?

SCOTT SHANE: Yes, there’s a genetic component to everything that people do, including entrepreneurship.

JOHN HENRY: That’s Professor Scott Shane, author of that study on entrepreneurship, and also author of the book Born Entrepreneurs, Born Leaders. That 2008 study was a twin study. It compared roughly 900 sets of identical twins to 900 sets of fraternal twins. And they found that yes. Your genes do make a difference in whether you’ll be an entrepreneur. Identical twins share identical DNA and fraternal twins don’t. This study found that identical twins, who, again, have the exact same DNA - are more likely to than fraternal twins to have the same job, including entrepreneurship. And so, the researchers deduced that there is a genetic component to entrepreneurship.

SCOTT SHANE: So we can explain a third of the tendency to be self-employed, to own a business, to be engaged in the business formation process as a function of their genetic makeup.

JOHN HENRY: So, according to Scott Shane’s study, roughly one-third of the tendency to engage in entrepreneurship comes from everything known as your genetics. Which ends up playing more of a role than other factors you might think of, like how much money you have in the bank...

SCOTT SHANE: The studies would show that having enough money, having enough savings, really accounts for less than 10% of whether or not a person goes into business for themselves. So by comparison we’re saying that genetic factors are substantially more.

JOHN HENRY: So this is our first lesson: Genetics matter. But, which genes exactly? Well, so far, these researchers have only identified one gene that they can pinpoint that has any relationship at all to entrepreneurship.

SCOTT SHANE: We found in fact that a particular version of the dopamine receptor gene affects the tendency to be an entrepreneur.

JOHN: Wow.

JOHN HENRY: A version of the dopamine receptor gene. If you have this particular gene, other studies show you need more stimulus or novelty to trigger the release of the brain’s feel good chemical, dopamine. The unscientific way of saying it is - your brain needs new experiences to make you happy.

SCOTT SHANE: One of the ways they might seek novelty is they might choose to go hang gliding as their sport of choice. Another way they might do it is to choose to start a business as their occupation of choice.

JOHN HENRY: It’s a good bet that Nsi, the guy we heard from in the beginning on Mt. Kilimanjaro, he’s got this dopamine receptor gene. So science gives us one answer: Your genes contribute to your tendency to be an entrepreneur... to the tune of 30-percent. But that means that the majority of what goes into being an entrepreneur has nothing to do with your genes.

SCOTT SHANE: Genes are not deterministic. All they are is affecting probabilities. There’s nothing that says that just because you have a particular genetic makeup, means that you could not become an entrepreneur. So the actual predictor is what do they do?

JOHN HENRY: In other words, if lesson number one is: Genetics matter. Then lesson number two is: Everything else about you matters way more. We know, from the research, that entrepreneurs tend to have certain personality traits in common: They have a need to achieve, they’re over-confident, optimistic, they take risks. But people who think a lot about entrepreneurship, the one thing that they seem to agree on is:

You can’t actually know for sure who’s going to be entrepreneur or whether someone’s going to be good at it. There was a really great discussion of this topic on the brilliant a16z podcast and it’s legendary Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen, who founded Netscape, among a bunch of other things. He’s talking about this very question. We asked a16z if we could use an excerpt here. You’ll hear a question to Marc Andreessen first and then his answer.

Q: What makes for a great entrepreneur? How do you evaluate it?

MARC ANDREESSEN: So this is the 64 billion dollar question and we talk about it endlessly. And it’s a very difficult question because the successes are so idiosyncratic. So I would say, there are many, many different kinds of successful entrepreneurs. If they were all MBAs or if they were all computer nerds or if they were all 14 or 28 or whatever it is, or 56, it would be so much easier. But in reality you just see all these, it’s just, it’s a game of exceptions. And you get all these stereotypes. You know, in 2004, in the same year, I’ll just give you two examples, diametrically opposed. Mark Zuckerberg drops out of Harvard, starts Facebook, age 20. With so little experience, not only has he not run a company before, he’s never had a job. On the other extreme, you had another great other software company called Workday that was founded by a famous legendary Valley entrepreneur named Dave Duffield, who had just turned 68, and it was his 7th startup, and it’s gone on to become a giant success. And so just even in that one year you saw this whole spectrum of age and experience. And so it’s heavily idiosyncratic. And there’s various kinds of models or templates that we can talk about when we get into the details but I would abstract a couple of really important things. So one, and this is the big one that we talk about a lot, which is this concept of courage. You all know all about it. But it’s this general concept of having the willingness to go hard against the grain for a long period of time. And in particular for entrepreneurs, it’s the willingness to be told ‘no’ over and over and over and over again. And this is the thing that people really miss I think. When entrepreneurship gets overly romanticized, this is the part that everybody misses. Just sort of the continuous soul-crushing misery of being shot down. And so, the willingness to be able to go out into the world and to be able to go appeal to people and go try to get people to do things and be shot down all the time and nevertheless to stay at it and power through it. By the way even once you get some people to say yes and once you get the company up and running, then things just go wrong all the time and so and even at scale it’s just crisis after crisis after crisis.

JOHN HENRY: And some people who could run companies, they choose not to, because they don’t want to put up with the crisis after crisis after crisis…

LOGAN ROCKMORE: I just want to be a cog in the machine. I want to be a small part of a large organization that’s doing something.

JOHN HENRY: That’s Logan Rockmore. He’s one of those people who rejected entrepreneurship when it came calling. Back in 2007, when the iPhone first came out, Logan noticed that there was something it didn’t do...

LOGAN ROCKMORE: I was at a San Francisco 49er’s game. I had my brand new iPhone. There’s no good website for me to check out the San Francisco Giants score. Woops. Better build something myself and it just kind of snowballed into this large thing.

JOHN HENRY: So he and his partner built that website where you could get live scores for all sorts of sporting events. And then in 2008, when apps became a thing, they decided to turn it into an app. This was so early on in the days of the iPhone that there weren’t that many apps out there. And so, Logan’s app, it was SportsTap, ended up being one of the first ones in the app store, and lots of people bought it, and before he knew it, Logan was running a successful company. Much to his dismay.

LOGAN ROCKMORE: I had no interest in being on-call a hundred percent of the time, making sure that this stuff wasn’t being inaccessible at any moment in time, so there was a long period of time where it was like, ‘Yeah, this sports app thing is kind of cool, but can I just go ahead and get rid of it so I can focus on my job at Apple.’

JOHN HENRY: Then came the tipping point, which made Logan realize he didn’t want to be running a business.

LOGAN ROCKMORE: Me and my father loved traveling around the country and visiting different baseball stadiums, ‘cause we love going to baseball games and I believe that this was, I want to say 2009, the last season that the old Yankee Stadium was open. And my dad and I wanted to travel to New York to see a game there before the stadium closed. And we had a trip planned and all sorts of tickets booked. And it turns out that that ended up being the first weekend of NFL season. We had signed some new advertising contracts and we really wanted to make sure that this was good money that we’d be getting in because NFL season is just such a huge boon for sporting apps and websites. So what we ended up doing was canceling that trip, making sure that I was able to be in front of that computer for the entire Sunday, from, you know, 7 AM Pacific time when people are starting to get up and look at predictions for the games and injury reports and things, all the way through until the final game was done at the end of the day.

JOHN HENRY: Logan wanted to go on vacation with his dad, more than he wanted to run a business. In many ways, a pretty simple decision. And so, in 2011, Logan and his partner sold the app to a Canadian sports company.

LOGAN: Do I have the urge to do it again? I went through this thing that was moderately successful and you know, I’m one-for-one. If I had some sort of real inkling, ‘This is in my blood and I want to do this,’ wouldn’t I take that money and turn that around and go with the many other ideas that maybe I have? I don’t feel that at all. And right now, I’m very happy working in a moderately-sized company, being able to contribute to some really cool products stuff, and I’ve no urge to kind of go be an entrepreneur again myself. I think it’s just there’s a lot of baggage that comes with doing all of that, all of that self-driven stuff. And I don’t want to have to worry about that. I’m able to focus more specifically on just the cool development that I want to do, that seems like a great win for my personal life.

NAZANIN RAFSANJANI: Hey John. It’s Naz

JOHN HENRY: Hey! What’s up Naz?

NAZANIN RAFSANJANI: Well, I should say first that I am one of your producers. I’m interrupting this episode for a second because listening to your interview with Logan, I felt like I really wanted to jump in and ask you if you’ve ever had that thought: I want to be a cog in someone else’s machine. Because you started your business, which was an on-demand, dry cleaning delivery business, you started that business at 19-years-old. You’re one of those people who has always wanted to run his own thing and you’ve always identified as a like, a born entrepreneur. So I’m curious like, have you ever had that thought: I just want to be one small part of someone else’s company?

JOHN HENRY: Yeah, for sure, yes. I remember like we got into three, back to back to back, car accidents. So like, we counted quite a bit on our delivery team and one of the incidents, it was actually my parents who like decided to take up a delivery and a cop car flicked on his lights and he t-boned my parents and our car. So there was that. And then, literally the same week…

NAZANIN RAFSANJANI: This is with your delivery truck, like your delivery cars, like your delivery cars where you’re delivering dry cleaning?

JOHN HENRY: Yeah. yeah. That one was my personal one...

NAZANIN RAFSANJANI: That was your personal one, ok, and then what happened?

JOHN HENRY: ...which doubled as a delivery thing. But then, the same week, I was in the car with my driver. We had just finished drop, I mean we finished a shift, and we finished dropping off our employee ‘cause it was raining so we didn’t want her to walk. And, I realized he was getting a little too close to the center of the road and he like drove head on into the pillar that holds the train up on 116th street. Boom! And it was just awful and I just remember getting out and that was like our actual van. And we pushed the car, and thankfully there was like a parking spot and I was like, ‘Dude, we’ll deal with this tomorrow.’ And then the next week, I needed to borrow my sister’s car to make that delivery and I remember I was turning off of the Brooklyn Navy Yard and I was at a red light in my sister’s car. And my sister was like, ‘Please, don’t ruin it.’ Like, you seem to have a curse with cars. And I was like, ‘Relax! I’m going to be fine.’ And I’m sitting, literally sitting at a red light, not even moving and I just remember actually having a thought, ‘Oh my God. We’re going to be ok.’ Because I was really stressed that like, we were down two cars, and that we had to pay out of pocket for both of them ‘cause they were our fault. And I just remember taking a deep breath and saying, ‘We’re going to be ok.’ And in that same instant an 18-wheel truck was making a turn and he didn’t calculate his turn right and he took the entire side of my sister’s car.

NAZANIN RAFSANJANI: Oh god.

JOHN HENRY: Yeah, I know. So it was in that, in those moment where it gets really intense that you’re just like, ‘Dude, I just want to, I wouldn’t mind just working for someone else right now.’

NAZANIN RAFSANJANI: Yeah. So then what happened? You just fixed all the cars?

JOHN HENRY: Yeah. You’ve got to put one foot in front of the other. Yeah. You just fix all the cars.

NAZANIN RAFSANJANI: God! God that sounds horrible!

JOHN HENRY: That was tough. I was so stressed that I was literally bleeding from my nose in the mornings. Can you believe that? I literally woke up and I was bleeding from my nose. And it’s because of like, the intense stress that you have going on. It’s definitely not healthy.

NAZANIN RAFSANJANI: Knowing what that experience was like, would you do it again?

JOHN HENRY: Yes. Yes.

JOHN HENRY: And this brings us to lesson three: The one thing that unites every successful entrepreneur...It isn’t genes, or personality traits, or how much you have in the bank even. It’s that to be an entrepreneur you have to really want it. A born entrepreneur wants to start their own business and get their big idea off the ground more than they want to do almost anything else. Even when doing that is really really hard. Corri McFadden EDROP-OFF founder and lifelong entrepreneur, just in the last few months, she’s had to: Chase shoplifters out of her store, she had to personally unclog the toilet in the staff bathroom several times. And when a pipe burst, in a storage room where she was storing lots of her designer inventory, in the middle of the Chicago winter, she had to put on her boots, in the middle of the night, suck it up and go straight there. It is constant, crisis after crisis, but she’s still doing it.

CORRI MCFADDEN: So like, I’m not going to sit there on Instagram and post me combining invoices, like hours upon end, or, you know, dealing with an overflowing toilet because everyone keeps flushing things down it. And we’ve told them a thousand times not to! Like all of those things that, you know, when you’re on an entrepreneur level. If I got to a huge level and I took a ton of VC and I added two layers of VP’s and a board and yeah, would I be doing those things, probably not. But I’d be dealing with other things. You never know what any day is bringing. Every day is different. Some days are super calm and you’re like, ‘Oh my God, is it coming?’ When you’re in your own thing, you’re running your own ship you’re still dealing with all the shit and it’s just, part of it.

JOHN HENRY: There is a genetic component to being an entrepreneur. But your genes don’t actually determine anything. The only real measure of what makes an entrepreneur an entrepreneur, is whether you’ve done it. Whether you had the courage to step out and give it a shot.

Open For Business is a branded podcast from eBay and Gimlet Creative.

Next week’s episode is all about one of the most fraught and confusing parts of starting a business: How to make sure you’re hiring the right people. We’ll hear stories of new hires gone terribly wrong and hopefully protect you against common hiring mistakes. That’s next week on Open for Business.

If you want to hear more about Open For Business visit ebay.com-slash-open-for-business, where you’ll be able to find more episodes of this podcast, as well as tools and information about how to start or grow a business on eBay.

Subscribe to us! Open For Business on iTunes or Google Play or anywhere you get your podcasts.

See you next week.

I’m John Henry. Thanks for listening.

Read Entire Transcript